About River Herring

River herring is a term used to describe two sea-run fish – alewives and blueback herring – that spend most of their lives at sea but return to streams and ponds to spawn. River herring are a keystone species in freshwater and marine systems, connecting communities and ecosystems upriver with ecosystems and food webs in the ocean. They are threatened by barriers to fish passage (e.g., dams) and climate change, but have seen a significant increase in numbers in recent years due to collaborative restoration efforts. In Maine, these fish are collaboratively managed by towns and the state, and are important ecologically, economically, historically, and culturally to many different stakeholders.

The Fish that Feeds All

The Passamaquoddy at Sipayik describe river herring as “the fish that feeds all”. These fish have provided an important source of food for thousands of years. Today, river herring are valued as bait for the lobster fishery, and smoked alewives (“bloaters”) have been enjoyed for generations in Maine.

River herring also play a key role in nearshore food webs, serving as connective tissue between freshwater, estuarine, and marine environments. When they leave rivers in the fall, they provide prey for marine fish like cod, haddock, and even bluefin tuna. Many birds also prey on river herring, including osprey, eagles, great blue heron, and loons. In fact, adult river herring may act as a “prey buffer” for endangered juvenile Atlantic salmon, providing an alternative forage resource for predators.

Blue heron preying on an adult alewife. Photography credits to Jon Albrecht

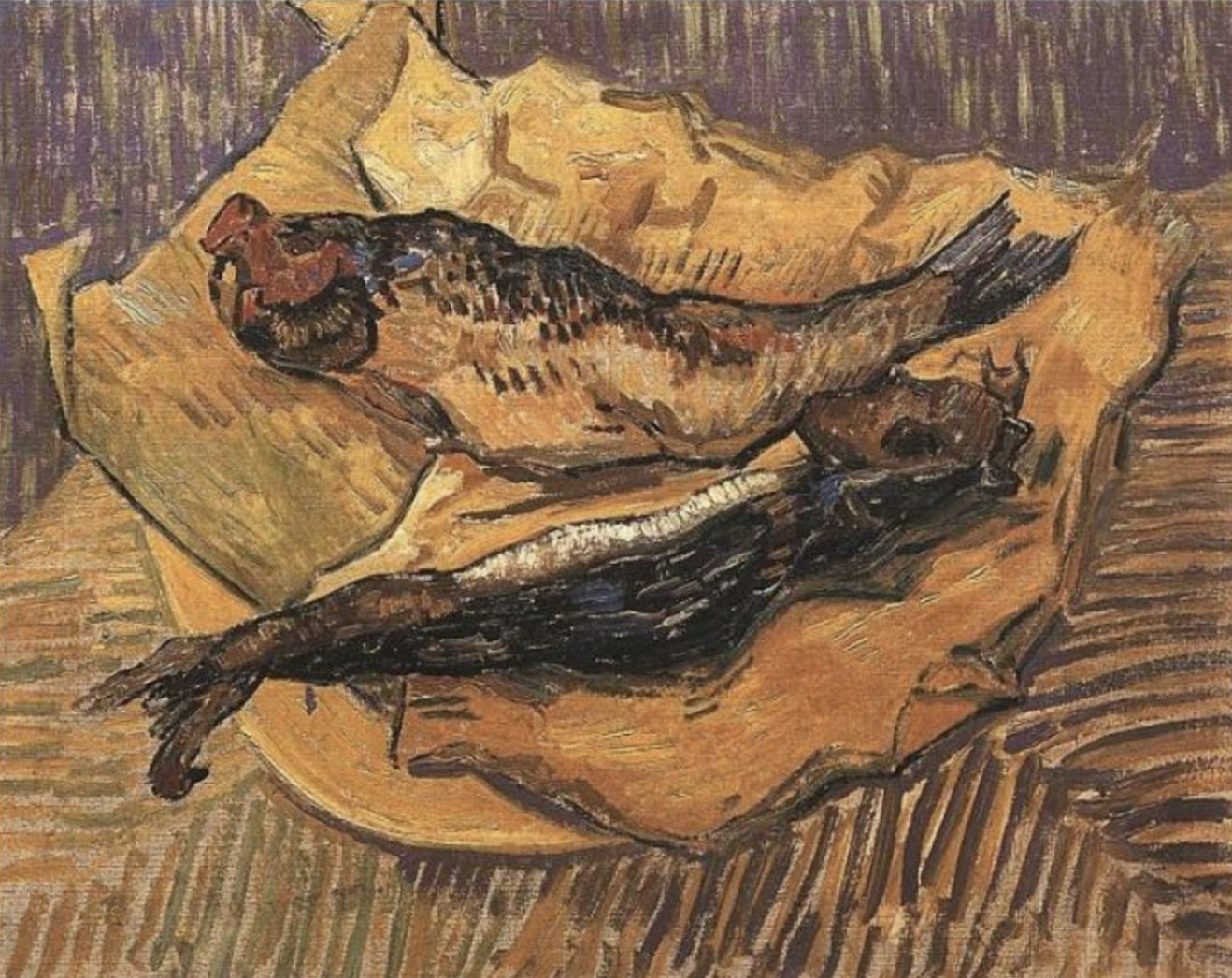

Van Gogh, Still Life: Bloaters on a Piece of Yellow Paper, 1889

River herring are an important source of bait for the lobster and halibut fisheries in the Gulf of Maine.

Pickled alewife. Photo courtesy of Barbara Tedesco

Harvesting alewife at Wight Pond, Penobscot, ME.

Juvenile alewife

Smoked alewives. Photo by Sarah Craighead Dedmon for Fishermen’s Voice

Conceptual life history of river herring, showing life stages, life stage durations, major life events, and habitats used. (Source: Hare et al. 2021)

Natural History

River herring spend most of their lives at sea, returning to coastal rivers each spring to spawn. Adult alewives swim upstream to spawn in lakes and ponds, while blueback herring spawn in the mainstem of rivers and streams. Most make this freshwater migration for the first time at four or five years of age, usually returning to the streams and ponds where they were born, though some straying does occur. Soon after spawning, they return downriver to the sea.

Juvenile alewives typically leave the ponds and lakes where they are born to enter estuaries in the summer and fall. There is significant variation in life history and habitat use, however – some juveniles spend longer in freshwater habitats (Payne Wynne et al. 2015), and many move back and forth between rivers and estuaries several times, rather than a single migration from river to sea (Stevens et al. 2021, McCartin et al. 2019). Once river herring leave the rivers and estuaries and move offshore for the winter, less is known about their at-sea migration patterns.

Challenges for River Herring

River herring face several challenges, including obstacles to fish passage, climate change, fishing pressure, and pollution. Before European settlers arrived in Maine, river herring were plentiful in the rivers and ponds, and provided a bountiful source of food for people and wildlife. Populations declined with the widespread construction of dams and pollution of waterways over the last two centuries. Today, dams and old or poorly designed culverts and bridges often prevent river herring from reaching their spawning grounds. Fishing by domestic and foreign trawlers in the 1960s contributed to the decline of river herring populations. River herring are currently caught as bycatch in Atlantic herring and mackerel fisheries, but efforts are underway to limit this incidental catch. Pollution from urbanization and industrialization also impacts river herring population health. Both alewives and blueback herring are considered to be very highly vulnerable to climate change, largely due to changes in water temperature and variable river flow, as well as the complexity of their life cycle (Hare et al. 2016). Despite these challenges, river herring are very responsive to restoration efforts, and their populations have started to rebound in recent years.

Co-management and Community Leadership

Fisheries collaborative management, or co-management, is a governance structure where resource users and governments share responsibility to manage a fishery. Learn more about the roles of federal, state, and municipal government, community members, and harvesters in collaboratively stewarding the river herring fishery.

The Fish that Feeds All - Video

Produced by Julia Beaty & Maine Sea Grant. Alewives and blueback herring are two ecologically and economically important species that can be found in Downeast Maine's rivers. The contents of this video reflect the perspectives of alewife and blueback herring harvesters and other community members who are working to restore and maintain healthy fish populations in Downeast Maine. This video showcases just a fraction of the valuable knowledge held by those who know more than anyone else about the fish in their local rivers. This video was produced as part of an oral history project carried out by Maine Sea Grant and NOAA Fisheries in the spring of 2014 with financial support from NOAA’s Preserve America Initiative. To learn more about the fisheries heritage of Downeast Maine, visit www.DowneastFisheriesTrail.org

Citations

Hare, Jonathan A., Wendy E. Morrison, Mark W. Nelson, Megan M. Stachura, Eric J. Teeters, Roger B. Griffis, Michael A. Alexander, et al. “A Vulnerability Assessment of Fish and Invertebrates to Climate Change on the Northeast U.S. Continental Shelf.” PLOS ONE 11, no. 2 (February 3, 2016): e0146756. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0146756.

Hare, Jonathan A., Diane L. Borggaard, Michael A. Alexander, Michael M. Bailey, Alison A. Bowden, Kimberly Damon-Randall, Jason T. Didden, et al. “A Review of River Herring Science in Support of Species Conservation and Ecosystem Restoration.” Marine and Coastal Fisheries 13, no. 6 (2021): 627–64. https://doi.org/10.1002/mcf2.10174.

McCartin, Kellie, Adrian Jordaan, Matthew Sclafani, Robert Cerrato, and Michael G. Frisk. “A New Paradigm in Alewife Migration: Oscillations between Spawning Grounds and Estuarine Habitats.” Transactions of the American Fisheries Society 148, no. 3 (2019): 605–19. https://doi.org/10.1002/tafs.10155.

Stevens, Justin R., Rory Saunders, and William Duffy. “Evidence of Life Cycle Diversity of River Herring in the Penobscot River Estuary, Maine.” Marine and Coastal Fisheries 13, no. 3 (June 2021): 292–305. https://doi.org/10.1002/mcf2.10157.

Wynne, Molly L. Payne, Karen A. Wilson, and Karin E. Limburg. “Retrospective Examination of Habitat Use by Blueback Herring (Alosa Aestivalis) Using Otolith Microchemical Methods.” Canadian Journal of Fisheries and Aquatic Sciences, March 19, 2015.https://doi.org/10.1139/cjfas-2014-0206.